Jean Toomer and Cultural Pluralism

[This short paper was originally written for “Jean Toomer and Politics,” a Special Session Roundtable at the 2012 MLA Conference in Seattle. I have made a few edits.]

In disagreeing with Rudolph Byrd and Henry Louis Gates Jr., I will not directly critique their support and rhetorical strategies. Instead, I will put forth my own interpretation of Toomer’s political vision. Toomer saw literature as his means to address socioeconomic inequalities, transform himself, and influence people in a manner that would advance the promise of democracy in America. We should ask then, not whether he identified as black or white, but what his political vision is, what it is not, and what it entails. Specifically, I argue that his political vision conflicts with the cultural pluralisms of his mentors, Alain Locke and Waldo Frank, and anticipates some postethnic, cosmopolitan, and multiracial perspectives that have emerged in recent history in strong opposition to the limitations and problems of multiculturalism.

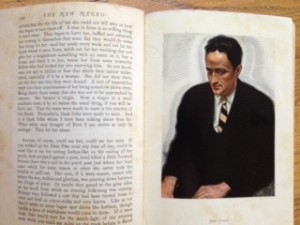

Winold Reiss’ portrait of Jean Toomer in The New Negro An Interpretation (1925) edited by Alain Locke

Horace Kallen and Randolph Bourne are usually given credit as the founders of American cultural pluralism, which we know today as multiculturalism. Between 1915 and 1916, both published influential articles in which they attributed the rise of segregation, nativism, and assimilation during WWI to the dominant Anglo-Saxon group. Both derided the notion of the melting pot as harmful and ineffective, harmful in that it promoted Anglo-Saxon homogeneity, ineffective in that some immigrant groups refused to be melted. In response, both articulated similar political visions of America as a harmonious federation of distinct national, ethnic, and cultural groups. In place of the melting pot, Kallen envisioned America as an “orchestra” of distinct and “autonomous” ethnic and cultural groups, with each group entitled to perfect its respective differences (“Democracy”). Bourne envisioned America more broadly as a trans-national, cosmopolitan “federation of cultures” that would recognize “dual-citizenship” and grant immigrants “free and mobile passage” between America and their countries of descent (“Trans-national”). He believed that “a younger intelligentsia” could do the work necessary to transform Anglo-Saxon America into a cosmopolitan American “tapestry” made up of “distinctive” cultural strands.

In 1916, Bourne also collaborated with Van Wyck Brooks, Waldo Frank, and others on Seven Arts, a short-lived literary magazine that published and promoted the creative, intellectual, and transformative work of the young American intelligentsia. In 1919, Frank contributed further to the realization of Bourne’s cosmopolitan vision with the publication of Our America, which recorded and discussed “adumbrated groups” and “buried cultures” in relation to the dominant Anglo-Saxon culture. Like Kallen and Bourne, Frank did not account for the Negro as a distinct cultural strand within the American tapestry. This omission created an opportunity for Toomer to re-present himself to Frank in his well-known letter from 1922 as an artist of black and white ancestry who could account for the Negro. That is, Toomer stated to Frank that he “missed” the inclusion of the Negro in Our America, and that he had included some of his own writings that were “attempts at an artistic record of Negro and mixed-blood America” (“Letters” 32). From 1922 through 1923, Frank would become Toomer’s close friend, mentor, editor, promoter, and have great influence over the content and structure of Cane.

Toomer’s attempt to account for the Negro was influenced by the cultural pluralist philosophy of his other mentor, Alain Locke. Locke became Toomer’s friend in 1919, and probably advised the young Toomer to lead a study group of prominent Washington Negro intellectuals, artists, and educators whose purpose in Toomer’s words “…[was] an historical study of slavery and the Negro…”(“Letters” 19). Known later as the Saturday Nighters, this study group interested Locke insofar as its purpose aligned with his cultural pluralist political goals. In his 1916 lectures on race, published in 1992 as Race Contacts and Interracial Relations, Locke sketched out on behalf of the Negro his own “doctrine” to counter segregation, nativism, and assimilation.

Like Kallen and Bourne, Locke believed that assimilation stimulated the Negro and other submerged groups to imitate and conform to the standards and values of the predominant Anglo-Saxon civilization type (Locke 90). To stem the “assimilative” tendencies of the Negro, Locke thought it was necessary to “make” and “promulgate” a “doctrine” of race pride, culture, and solidarity. That is, he proposed a politics that would “[dam] up the social stream” and “stop the egress” of Negro talent and cultural products by “harnessing” partly-assimilated Negro individuals and classes “to the submerged group” until such a time in the future where the Negro race would be recognized and respected as a distinct cultural group on par with other cultural groups within a democratic cosmopolitan federation (97-98). According to Locke’s cosmopolitan political vision, the Negro group, having attained “culture-citizenship,” would then be able to contribute its own representative cultural products “in terms of the group’s own estimate” (99).

Toomer and his mentors embraced opposing views of amalgamation. In Locke’s view, amalgamation hastened the pace of social assimilation to the dominant Anglo-Saxon type, and necessitated a politics that would inhibit amalgamation by creating an “artificial barrier” and by educating the new Negro group (Locke 98). Likewise, Bourne viewed amalgamation as a threat to ethnic and cultural groups insofar as it created “…masses of people who are cultural half-breeds, neither assimilated Anglo-Saxons, nor nationals of another culture” (“Trans-national”). Though Frank was more optimistic about the prospects of “cultural half-breeds,” he also envisioned America’s ideal future through cultural pluralist terms and assumptions.

In contrast, Toomer resisted the cultural pluralist dictate that amalgamation means assimilation to the dominant Anglo-Saxon group. He also questioned the cultural pluralist assumption that amalgamation sustains Anglo-Saxon values, interests, and standards. In his 1929 essay, “Race Problems and Modern Society,” he suggested that “big business” and social-political institutions, not the Anglo-Saxon group per se, had already changed the American nation into “…a social form containing racial, national, and cultural groups…” (69). He viewed this development as “a social trap” for “all Americans…the white no less than the black, the black no more than the red, the Jew no more than the gentile” (72). He predicted correctly that established group divisions, distinctions, and antagonisms would become more pervasive and intense as “big business” and “American institutions” continued to grow and extend their reach (72).

In further contrast to his mentors, Toomer believed that amalgamation actually might help reconcile racial group divisions and antagonisms, and thus contribute to the making of a new America. His attempt to foreground amalgamation anticipates the postethnic perspective of historian David Hollinger, and specifically Hollinger’s point that amalgamation needs to be recognized as a major theme in the history of the United States (“Postethnic” 33). Toomer believed that a growing solidarity of new Americans conscious of the historical and empirical reality of amalgamation could do the work necessary to renew American democracy.

Toomer’s new America would uphold Hollinger’s principle of affiliation by revocable consent, so that Locke’s value imperatives of respect and intercultural reciprocity would apply not just to ethnic and racial groups and their membership, but also to individuals who wanted to identify and affiliate themselves concurrently with multiple descent groups and with larger collectives such as the American citizenry and the human species.

Byrd, Gates, and other naysayers have dismissed Toomer’s vision as mystical, self-centered, and wrongheaded. Their interpretative strategies typically involve associating him with what Hollinger calls the “fantasy of amalgamation,” which is the general idea that an increase in the number of interracial marriages and mixed-race people will solve the race problem and advance humanity.

In actuality, Toomer was not that naïve. His post-Cane writings evidence that, even during the Gurdjieff years, he did not waver from his subtle, complex, and socialistic view that “existing economic, political, and social systems” in America render cultural, ethnic, and racial groups “divided and repellent” (“Race Problems” 69), and compel citizens to “…put value upon, their hearsay descents, their groupistic affiliations” (“Wayward” 121).

In conclusion, his ugly breakup from Locke and Frank does not indicate his ingratitude and arrogance, but rather his eventual realization that their pluralist sensibilities and politics were at odds with his vision for a new America. In other words, he realized that a solidarity of new American individuals would ultimately need to disaffiliate from “…the old terms for old races,” and no longer view itself as “part white, part black, and so on” (Rusch 107-108)—then perhaps over time the American state might evolve into what Josiah Royce termed a beloved democratic community—which would entail a great deal more social and institutional respect for individual differences and rights versus the politics of perpetually dividing and classifying individuals within racial and ethnic groups to advance the interests of group leaders, big business, and politicians.

Works Cited

Bourne, Randolph S. “Trans-national America.” The Atlantic, 01 July 1916. Web. 16 Mar. 2014.

Frank, Waldo David. Our America. New York: Boni and Liveright, 1919. Print.

Harris, Leonard and Charles Molesworth. Alain L. Locke: Biography of a Philosopher. Chicago: Chicago UP, 2008. Print.

Hollinger, David A. Postethnic America: Beyond Multiculturalism.1995. 10th anniversary ed. New York: Basic, 2005. Print.

Kallen, Horace. “Democracy Versus the Melting Pot.” The Nation (1915): n. pag. Pluralism and Unity. Web. 16 Mar. 2014.

Locke, Alain. Race Contacts and Interracial Relations: Lectures on the Theory and Practice of Race. Ed. Jeffrey C. Stewart. Washington, D.C.: Howard UP, 1992. Print.

Toomer, Jean. Cane: Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism. Ed. Rudolph P. Byrd and Henry Louis Gates Jr.. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2011. Print.

…Jean Toomer: Selected Essays and Literary Criticism. Ed. Robert B. Jones. Knoxville: Tennessee UP, 1996. Print.

… The Letters of Jean Toomer: 1919-1924. Ed. Mark Whalan. Knoxville: Tennessee UP, 2006. Print.

…The Wayward and the Seeking: A Collection of Writings by Jean Toomer. Ed. Darwin T. Turner. Washington: Howard UP, 1980. Print.