On Growing up Mexican Italian American

[This piece was originally published in January 2018 by The Parent Voice, an online journal that no longer exists. The layout and some of the photos in this version are different.]

I became aware of the world around me during the Reagan era in a middle-class, conservative, predominantly white suburb of Los Angeles. Growing up Mexican Italian American in this context was difficult and dissonant for me. If I had grown up in a different place or class, my mixed experience might have been very different, but then I would not have this story to tell.

My mother is the youngest daughter of immigrants from Mexico, the first in the Chavez-Rios family to graduate from high school. Her father Philippe Rios crossed the border as a boy with his family in the late 19th century. They settled in South El Paso, Texas. Phillipe migrated to Los Angeles as a young man and worked his way up in the steam laundry industry. Years later, he married Elvira Chavez whose path to America was far easier than his was. In the 1920s, she simply boarded a train from Parral, Chihuahua to Los Angeles Union Station and moved in with a relative.

My father Gino, the son of Clinio Pellegrini and Edda Dal Bianco, was born during WWII in Lugo di Vicenza, Veneto. At seventeen, he immigrated to America to work and to pursue a career in the arts. He studied at various arts colleges in Los Angeles. He then attempted to obtain US citizenship by being legally adopted by his hosts, the Markham family. This attempt was unsuccessful, but he continued to use their name, feeling that Italian immigrants were still targets for discrimination and that he could secure more work in Hollywood with an Anglo-Saxon last name.

My mother was engaged in a dance career and working full-time when my father came into her life. He was working in crews that prepared sets and painted backdrops for television shows like H.R. Pufnstuf and for movies like 2001: A Space Odyssey. When they married in 1968, both appeared to be in pursuit of the American Dream. He was making good money. He would become a US citizen, move forward in Hollywood, and be credited for the work that he did. They bought a house in the suburbs, one with a family den and a detached two-car garage in which he could do his art.

My father, however, grew tired of his life in Los Angeles and of the idea of working for Hollywood capitalists that would continue to dictate the form and content of his art. So, my parents rented the house and moved to Italy so that he could create artworks that were more socially conscious and committed. Unfortunately, art projects that paid well were few and far between, and the lack of money increased family tensions. The family fell apart in 1972 when I was one. My mother returned to Los Angeles with me. I am the product of this failed international, multiethnic marriage.

Back in Los Angeles, we lived in various apartments in the Mid-Wilshire district because the city was where my mother could find full-time work. I was happy living in the city. However, when it was time for me to start kindergarten, my mother decided to move back to the house in the suburbs for presumed better schools in a safer, cleaner, whiter neighborhood.

My best friend in kindergarten came from a somewhat similar mixed background as I. His mother was an immigrant from Argentina, and his father came from Sicily. We played on a few soccer teams together, and remained friends through the fourth grade. I liked to go over their house for playdates and holiday get-togethers. They had MTV, Atari, and a large backyard. The biggest problem with this friendship, from my perspective, was his older brother (three years older) who was totally into Duran Duran, and, for a short while, Mein Kampf. In my eyes, he was about a foot taller than me with thick, wavy, sandy-brown hair, a light complexion, and a bad case of acne. He wanted to be on team white, and he did not like to be reminded that he was part Hispanic and the son of a dark-skinned southern Italian. Spic and beaner were words that he casually used, and when he became annoyed by my presence and appearance, he did not hesitate to call me an ugly and stupid beaner too.

Growing up, I sometimes needed to explain to curious classmates and adults why my physical appearance did not match up with my Anglo-Saxon last name. Questions that they asked included: Do you have a stepdad? Were you adopted? Where are your parents from? If asked respectfully, I was happy to explain that my father was an artist and lived in Italy and that my mother’s parents came from Mexico, but my honest explanation typically generated expressions of miscomprehension, doubt, and an occasional that’s cool. In this time and place, the custom or norm was to [identify] others and oneself in monoracial, monoethnic or national terms. Hence, for want of others in this context willing to model or validate mixed and multiracial identities, the notion that I could publicly claim a mixed identity remained cloudy in my adolescent mind. I tended to vacillate in silence between the established monoracial, monoethnic, and national terms that were applicable to me.

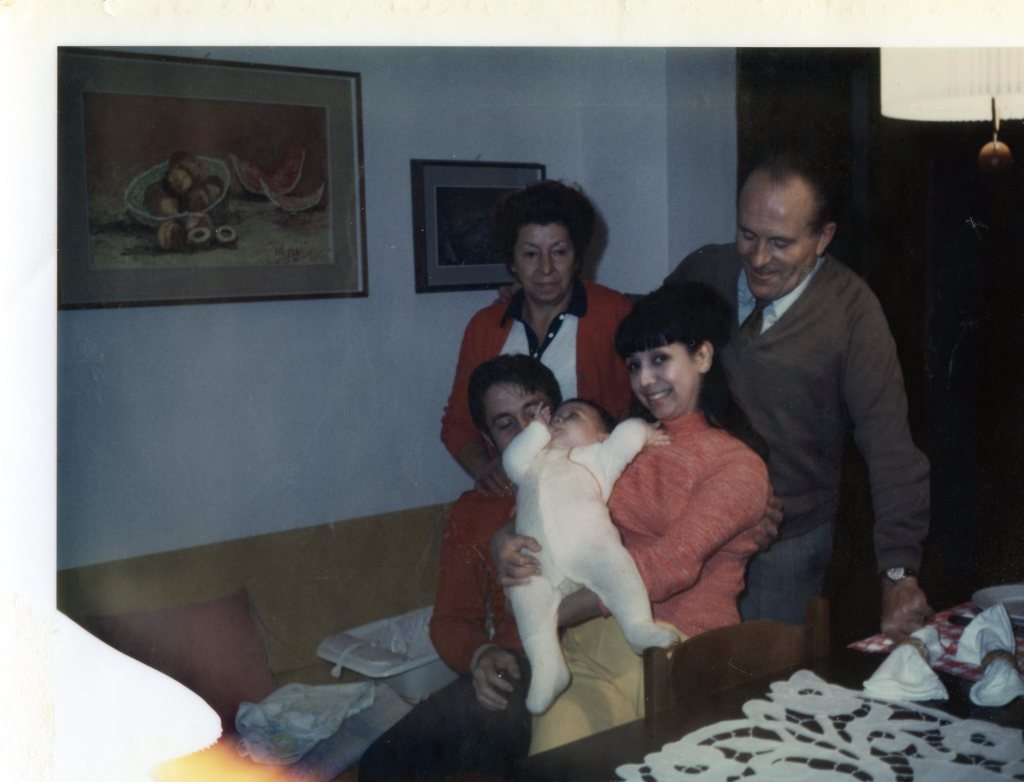

As a kid, I yearned to spend more time with my Mexican and Italian relatives, however the money needed to travel was almost always lacking. Unlike some international, multiethnic Third Culture Kids (TCK) with professional-class parents, I was a latchkey kid with an absent Italian father and a mother who often needed to work two jobs to pay the mortgage and utilities. My Mexican grandparents unfortunately had passed away before I was born. Relatives from Mexico visited us every now or then, or we would meet them in between. Besides these few encounters, my knowledge of my Mexican family came from family photo albums, artifacts, and stories told by mother about her parents, aunts, and uncles. Regarding my Italian family, my father did not have much money, and he did little to help me stay connected. Worse, when I was in the third grade, he stopped writing letters, calling, and sending postcards altogether. Fortunately, my Italian grandparents called and wrote to me regularly, and I stayed in touch by phone with my uncle, aunt, and cousins. More significantly, my grandmother travelled to Los Angeles a few times to spend time with me. Her love and consistent communication with me via phone, letters, and photos helped me sustain a sense of also being Italian.

In middle school, I played on the basketball team, but I was also friends, not with the punk rockers, mod revivalists, heavy metal kids, Madonna wannabes, born-again Christians, or student leadership kids, but with the break-dancing crew. I sucked at break dancing, but I was good at carrying a boom box and at cheering on my friends who were good break dancers. The kids in this group, like my other few close friends after the third grade, were my complexion or darker. I liked being friends with these kids, especially when we would ride our bikes far away to parks and schools in neighborhoods far more diverse than ours to challenge other break dancers, play hoops, or to just hang out.

In high school, I gradually withdrew socially as I became more aware and resentful of the ramifications of growing up poor with an absent father within the conservative, white, middle-class suburbs of Los Angeles. In my freshmen year, I accepted the view that the burly, Germanic-looking white men in positions of authority—coaches and administrators—were models of good American citizenship. However, I became fed up with their careless, condescending, or chauvinistic comportment toward minorities. Most of these white men became objects of my derision in my final two years of high school. I swore to myself that I would never become like them. Unhappy and angry about my situation, I continued to play basketball and run distance, but I was absent from school more and more. I did not want to be there that last year; I barely passed my required classes. Skipping my high school graduation ceremony was my final act of social withdrawal.

Fortunately, my desire to investigate and reclaim my entire heritage also grew exponentially during my final two years of high school. I was hungry for culture, and I was determined to embark on a personal journey of cultural reclamation by first tracking down my father and spending time with him and my other Italian relatives. Of course, I had to work as a temp for about six months after high school to earn the money that was needed to travel to Italy. The time I spent with my family and my father in Italy showed me that it was possible to develop an international, multiethnic sense of self. Back in Los Angeles, I started college with this possibility in mind, expunging my old Anglo-Saxon last name from all official records, and starting down the path of forging a public mixed identity.

Much has changed in the world since I was an ambivalent and angry mixed kid growing up in the conservative white suburbs of Los Angeles during the Regan years. For one, these suburbs are now predominantly Asian. Today I am totally at peace with the circumstances of my upbringing and my difficult mixed experiences growing up. I might not be in the good place that I am today without them. More importantly, they gave me purpose and motivation to create a mixed identity that has also been a means for me to engage and to have a public voice on issues such as monoracialism, white normativity, colorism, institutional racism, and other effects of the history of white supremacy. Moreover, I am now a professional-class parent with my own very mixed child who also has an Israeli grandmother and cousins. I feel privileged to be in a position to support her as she navigates through her own identity challenges in this age of Trump. My hope for the future is that as more people cross established lines of race, ethnicity, and nation to form unions with their loved ones, more communities, institutions, and nations will choose to validate and support the lived realities and identities of emergent multiethnic/multiracial families and individuals.